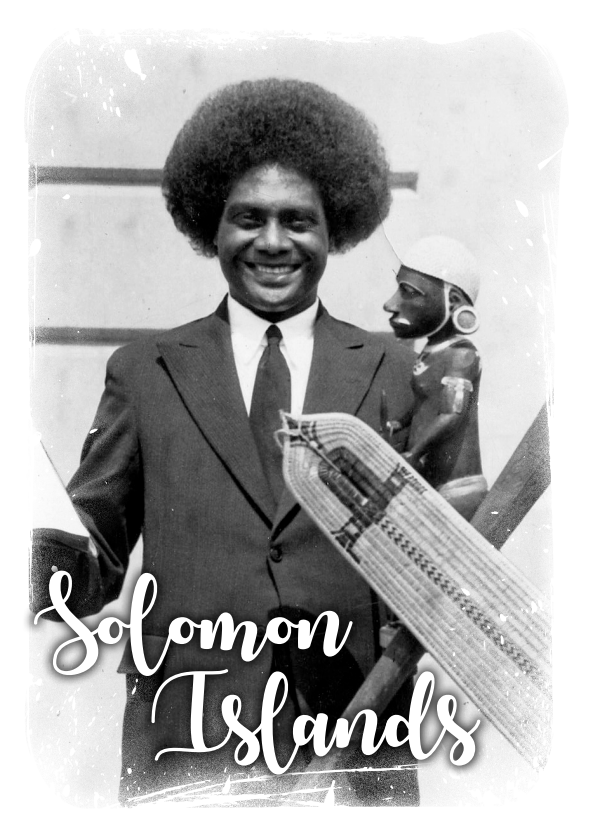

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands and their missionaries

It was Sabbath School and Missionary Volunteer offerings that provided the means of establishing the missions in the Solomon Islands, sponsoring many of the mission boats that plied the islands. It was one of these boats, the Advent Herald that was instrumental in exploring and setting up mission stations throughout the Solomon Islands, when in 1914 seasoned missionary Captain Griffith Francis Jones and his wife Marion travelled to the Solomon Islands. Not only was he a Master Mariner, he was a gifted linguistic, a trail blazer for Adventists missions throughout the South Pacific.

In 1916, with money raised from by Adventist youth in Australia, Jones organised the purchase of a large boat, the Melanesia, and embarked on mission work. The Batuna School, with its associated printing press and medical clinic, located between New Georgia and Vagunu Islands in the Marovo Lagoon, was the mission headquarters and was soon producing church workers. Chiefs and influential land-owners were impressed with the cleanliness of the mission and their use of English.

In 1917, the Melanesia commissioned. Built in Sydney, she was a little more than 18m long with a shallow draught to allow sailing amid shoals and reefs. The Melanesia logged nearly 30 years of service, with Jones sailing her as far as Vanuatu and Papua and New Guinea.

Baptisms were held throughout the country as the missionaries broke down old animosities, and to foster a church community spirit. Many of these new converts proved to be the strength of the Mission. They were young, zealous and dependable, and despite a lack of formal education and training, many achieved amazing results. It seems that music and the singing of gospel songs greatly impressed the Solomon Islanders. Many of the converts used their love of music to reach people.

To enable Nicholson to move quickly about the lagoon and visit the pockets of interest a motor dinghy was fitted out in Sydney and shipped to him. He named it Minando. The little vessel allowed the missionaries to move from station to station providing spiritual, pastoral and education guidance.

With 1920 came considerable changes in European staffing: the Nicholsons transferred to Vanuatu, the Joneses found it necessary to retire from the tropics; and Gray was confined to the Sydney Sanitarium suffering with blackwater fever. All of the pioneer missionaries experienced repeated bouts of malaria, dangers on the stormy seas, primitive housing facilities and isolation. They grappled with the daily problems as best they could, sometimes having to make decisions without advice from their colleagues.

The first decade of the Solomon Islands Mission saw the establishment of key stations staffed by a European couple. At these places young men were briefly trained to care for branch stations. At times they would only stay at one outpost for a few months and then return to school for more training while another student replaced them. Their limited resources were a Sabbath School picture roll and translated Sabbath School lessons.

It soon became obvious that the Solomon Islands’ expanding number of missions desperately needed a central training school. Batuna became the training school. A printing press donated by the Signs Publishing Company to foster more translation work, printed Sabbath School pamphlets, along with larger works, including two hymnbooks.

Other major developments in 1924 were the pioneering of Bougainville and Malaita Islands. When in October 1927, two government officers and most of their police guard and boat crew were murdered while collecting taxes not far from the Andersons’ station, the Anderson family lived on their little boat the Advent until calm was restored.

By 1929, Batuna School was producing many church workers. Other expatriates followed, continuing to expand the outreach of the church and the establishment of schools. By 1930, there were almost 600 baptised members in the Solomon Islands. This figure then doubled before World War II and increased even more rapidly after the war. The Solomons proved to be one of the most responsive groups in the South Pacific. The requests for village missionaries were numerous and persistent, some having to wait years for their wishes to be realised. The mission superintendents gradually trained their own workers rather than import converts from other island

groups.

The people themselves observed the lifestyle at the Adventist mission stations. Their favourable impressions were passed on by word of mouth. Gospel singing proved to be an entering wedge. Literature was not so much a factor in the early years. Repeatedly the name of Jesus was used to bring victory over evil spirits. The islanders also grew to value the peace which came to their society when Christian love was practised. The days of murderous head-hunting, human sacrifice were over.

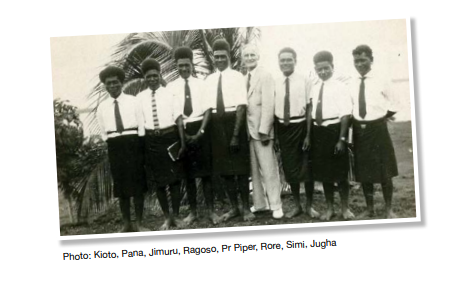

Jugha

When a small boy, Jugha was captured by warrior Chief Tatangu. Instead of being sacrificed, the chief took him into his home and raised him as one of his own sons—Kata Rangoso and Peo. When the Seventh-day Adventist mission established the Batuna Training School nearby, the boys were among the first students.

In 1918, a few young men from Ghoghombe had travelled to Kolobangara Island looking for employment at a coconut plantation. While working there, they came in contact with the Seventh-day Adventist Church. The men were enchanted with the singing and wonderful atmosphere. When the Methodist Church sent its missionaries to Choiseul, the villagers sent them away, saying that they were waiting for their men to return with knowledge of the “singing church.” When they returned, they convinced the chief to ask for a “Seven Day” teacher. It was Jugha who was sent, and in 1921 disembarked at the southern tip of Choiseul.

A number of villages in the area were anxious to accept Jugha, but the place chosen for the mission was Goghobe. The only implement Jugha owned was an axe. He was given some packets of nails, a hammer, and a saw, then set about building a house and a church from materials gathered locally. A ship had been wrecked nearby the previous year and large quantities of sawn timber had drifted ashore. Jugha salvaged ebony for the foundations and Philippine mahogany for his flooring and seating. Within the year a congregation filled the church and he was conducting a day school.

He achieved dramatic success in just one year. He recognised how it was singing that they loved; he used it as a means to teach correct behaviour and to change beliefs and values and a healthier way of living.

Due to his positive influence, the majority of the villages in northeast Choiseul became Adventist, with many becoming future missionaries for the church. Sogavare became a missionary to Papua New Guinea; Pastor Samson Sogavare became an evangelist and his brother Moses likewise; Manasseh Sogavare became a politician then Prime Minister of the Solomon Islands; Rayboy Jilini became a mission director and evangelist; Pastor Tanabose Lulukana became a pioneer missionary and mission director; Pastor Lawrence Tanabose worked in the Union and in the South Pacific

Division administration in Sydney; Pastor Caleb Ripo became a district director and evangelist; Mr Gilakesa became an influential teacher; Chief Teddy White was church teacher; and Mr Leleboe was a long-term church employee.

Jugha had a great influence, beginning then establishing the work of the Seventh-day Adventist church that continues today.

Meri and Simi

In 1929, Pastor Simi and his wife Meri, local Solomon Islanders working as teachers with Pr J D Anderson, were clubbed to death while working in their gardens on Malaita. The attackers left Simi for dead, but he survived. However, Meri died. The attack was meant to deter the work of the church, but it resulted in just the opposite happening. The church work expanded.

Pana

Pana may have been born a head-hunter but he became a heart hunter. Pana was convicted to become a Seventh-day Adventist when missionaries told him the story of courageous Deni Mark, a Solomon Islander who was killed by the Japanese when he was acting principal at Kambubu, on the island of New Britain, off the north coast of New Guinea. Following his conversion, he become a great evangelist.

In 1953, he and Pastor Itulu visited an Adventist woman and her husband the local chief, and a couple of other people on the Weather Coast of Gizo Island. They conducted the Week of Prayer in the house of the chief’s wife. Even though the Methodist teacher was not happy to have the “Seven Days” in his village, he couldn’t disagree with his chief. When the Methodist council wished to have chief dismissed, the chief exclaimed, “If you do that, I will go also and become an SDA.” He continued, “I will not promise to be an Adventist myself but I will help my wife to be a good one . . . I want them to go to heaven and I know that they have the true way.” Pana continued to visit the chief to help him.

This evangelistic spirit was always with Pana. When Pana became sick, he was sent to the Methodist Hospital. While sick in bed, Pana still told people about the love of Jesus. Pana won a patient, a leper who was the chief’s wife brother, to the Adventist faith. This man, Jonathon, then returned home and converted many of his villagers. Whoever Pana met, he introduced them to the Lord.

One man can make a huge difference.

Reference:

Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm. Pp. 47-50.

Kata Ragoso

Pastor Kata Ragoso, a natural leader, was left in charge of the Adventist work in the Solomon Islands during the Japanese occupation of World War 2. Ragoso later said that during the times of greatest opposition from the enemy forces, the tithes and offerings were the highest with little backsliding of members. When members were forced to close their churches and schools, they met in caves and in the bush, continually moving to safer places. Under the most trying conditions, Pastor Ragoso, with help from faithful workers, protected the mission property. He maintained the church’s machinery and infrastructure, for example concealing the Portal up a creek

away from the Japanese.

With his strong connection with repatriated Australian and New Zealand missionaries, he assisted Allied servicemen shot down or adrift from sunken ships. At first, the Allies were suspicious of this man who refused to work on Saturdays, which resulted in his being whipped, even facing a firing squad.

Rangoso and his “Marovoa Lagoon boys” are best known for hiding downed Allied airmen until they could be rescued, often to Major Donald G Kennedy of the Coast Watcher network. Even though Kennedy had tried to force the Rangoso and many of the Adventist boys to work for him and on Sabbath, leading to punishment, the Adventists were still willing to assist the Allies.

Kata Rangoso was highly respected by both his countrymen and expatriate missionaries. He demonstrated true humility, great love and great energy in serving his Lord.

Reference:

Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm. Pp. 44-46.

SDAs in the South Pacific 1885-1985

First church in Australia

On May 10, 1885, 11 Americans set sail on the Australia from San Francisco, USA, with plans to establish the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Australia. The pioneer workers included Pastor Stephen Haskell; Pastor Mendel Israel, accompanied by his wife and two daughters; Pastor John Corliss, accompanied by his wife and two children; Henry Scott, a printer from Pacific Press; and William Arnold, a colporteur.

They arrived in Sydney on June 6, 1885. While Pastors Haskell and Israel stayed in Sydney, the others continued aboard a coastal steamer to Melbourne, which had been selected to be the base for the Church’s Australian activities as there were rumours of Sabbath-keepers living there. They formed the first Seventh-day Adventist church in Australia in Melbourne on January 10, 1886, with 29 members.

First church in New Zealand

Pastor Haskell, who was keen to spread the message in New Zealand where the pioneers had called on their initial voyage to Australia, returned to Auckland and began distributing the Church’s outreach publication The Bible Echo and Signs of the Times. Reports of Haskell’s successes in New Zealand caused the leaders of the Church in America to delegate A.G. Daniels, an evangelist, to travel to New Zealand to develop the work further. Daniels, an enthusiastic preacher, had great success and in 1887 opened the first Seventh-day Adventist church in New Zealand at Ponsonby. Daniels would eventually go on to become the world president of the Seventh-day

Adventist Church.

First Adventist contact in the Pacific Islands

In 1886, John I Tay, an American layman, reached Pitcairn Island aboard a vessel of the Royal Navy. He stayed on the island until another ship arrived. Tay’s simple teaching fascinated the islanders as the message matched with the message of literature—Signs of the Times—sent years previously from America by James White and John Loughborough. Within weeks, the slanders accepted the suite of Adventist truths. When Tay left, he promised to send someone to baptise the group.

Upon his return to America, Tay’s accounts inspired other Adventists to visit Pitcairn. One, Pastor Andrew J Cudney, found an old schooner, the Phoebe Chapman, and he and a crew sailed for Tahiti where they planned to pick up John Tay before sailing to Pitcairn Island. Sadly, they never arrived, as the ship was lost at sea.

Tay was anxious to return to Pitcairn Island and a boat was required. Funds from Sabbath Schools across America raised money for one, the aptly named Pitcairn, which under Captain Joseph Melville Marsh, was ready to sail in October 1880. Tay was joined by two other enthusiastic missionary couples, Edward Gates and the Albert J. Read, who were greeted enthusiastically by the islanders on Pitcairn. Eighty-six people were baptised and a church formally organised.

When the Pitcairn departed the island three weeks later, on board were three Pitcairn islanders who wished to spread the Adventist faith. As the ship travelled westward from island to island, literature was distributed, evangelical meetings held and medical treatments dispensed. After visiting Papeete, the Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga, Fiji and Norfolk Island, it arrived in Auckland, New Zealand. There they heard the news of Tay’s death in Fiji. The Pitcairn returned to California, carrying missionaries on five more Pacific voyages.

Early Australian and New Zealand Missionaries to the Pacific

As a result of the four voyages from America into the Polynesia, missions were established in Pitcairn, Tahiti, Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga and Fiji. Most of the next wave of missionaries had their origins in Australia and New Zealanders. But the work was difficult and met with resistance, with the London Missionary Society and Roman Catholic Church having made the initial impact on the islands.

The advancement of the Church work in the Solomon Islands expanded dramatically after World War II with the return of former and new Australian and New Zealand missionaries, all with the aim of supporting the local Solomon Island missionaries. Many new initiatives were put in place.

Betikama Missionary School

When Allan Thrift arrived in Guadalcanal in 1948, he was charged with establishing a school in “Sun Valley,” so named by the US marines who had been established there, which would become Betikama. Most of the building materials for the school came from the US Army. At first classes were held at night, as during the day the students and staff built the school and established gardens. This program changed as the school developed. Many of the students came from different language and cultural groups throughout the Solomon Islands, and some students were older than their teachers. Eventually girls were introduced into the school. Thrift, Pastor Kilomburu Liligeto (Kata Rangoso’s brother) and Laejama managed the school. Their responsibilities increased with the transfer of the printing press from Batuna. Food during the week was very basic, with sweet potato or tapioca twice a day. On non-school days the students provided their own food from their individual gardens or caught fish from the nearby Lunga River. The purpose of this school was to provide church workers for the increasing number of mission stations. A partial list of Betikama pioneer missionaries includes Vavepitu to New Guinea; Isaac Moveni, Solomon Islands; Jioni Pao, Nathaneel, Jacob Makato, Jacob Maeke, Kituru Ghomu, Elisha Gorapava, to New Guinea; Thurgea, Wilfred Bili, to PNG and Australia; Nathan Rore, to New Guinea; Saronga, and Thomas Gree.

Atoifi Hospital

In 1951, the Amyes Memorial Hospital, built from funds donated by an early

Adventist family in Christchurch, New Zealand, was extremely busy. It was staffed by two Australian nurses and six indigenous assistants. Another busy Adventist hospital at Kwailibesi in Malaita was developed by a missionary wife and doctor, Dorothy Mills-Parker. Both these institutions have been replaced by Atoifi Hospital at Uru Harbour on the eastern coast of Malaita. As the work of this hospital expanded and more overseas workers came to work in the hospital, some resentment to the church was aroused. Brian Dunn and his wife Valmae, recent graduates of the Sydney Sanitarium, accepted the call to serve as the first nurses at the hospital. They enthusiastically left Sydney in November 1965, to begin work at the Malaita Hospital. One night, while returning home after an emergency medical callout, Dunne was struck by a spear in the back near his house. The spear was thrown with such force that it went through his body and protruded through his chest. Dunn was transferred to Honiara, where the spear was removed. Despite the operation appearing to have been successful, Dunn passed away on December 19, 1965.

Police quickly apprehended two suspects, one a devil priest, Endaie, who had asked his nephew to kill Dunn. The devil priest was resentful for his lack of recognition, but also believed he had not received a proper share of the funds from the sale of the hospital land. The death of Brian Dunn was his retribution on the hospital. While Dunn’s death was a great loss to the Church, the hospital continued to serve the people in the district.

Reference:

Steed, E. H. (2012). Impaled: The story of Brian Dunn, a twentieth-century missionary martyr of the South Pacific. Nampa. ID: Pacific Press

Piez, E. (2007). Atoifi Hospital, Malaita: its planning, construction and opening in the 1960s. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 7(1), pp. 19-27.

Dissemination of literature

In 1952, the British and Foreign Bible Society took over responsibility for printing the Morovo language Bible translation prepared by Tasa, Barnabas Pana, Pastor Rini and Pastor Robert Barrett. These Bibles were effective in spreading the message of the SDA Church. The urban areas also had literature evangelists selling literature from village to village.

Prior to the war, the Adventist church had established a scattering of mission stations not far from the coast. As Australian and New Zealand missionaries returned and joined in partnership with local Solomon Islanders, the work of the church expanded.

SDA mission post-WW2

Ngodore Sogavare Loko

In the Thirties, after being educated at the Batuna School, Sogavare Loko worked for a number of years as a teacher in the Solomon Islands. He with his family were sent to Papua, where they were stationed at Mirigeda while studying the Motu language. By mid-1935 Sogavare was teaching at Domara School, preparing students for government examinations. His influence was such that calls for teachers came from other villages in the area. He helped to break the power of puripuri (sorcery), burning the objects related to its practice. He even took a sorcerer to court in Abau. Where the

government official was about to jail the offender, Sogavare asked for a second chance for the man, who eventually became a good friend.

Pastor Taumai, a former Domara student of Sogavare, recalls that Sogavare was a hard-working man, who, as well as teaching, preaching and supervising work activities, taught the people of Domara how to make soap and how to build a faster Solomon Islands-type canoe.

Sogavare’s wife, Hezilyn, was noted for her musical abilities, her lovely singing voice, and devoted care of her family.

During the war years, Pastor Sogavare saved the lives of many Australian soldiers. He continued his work in Papua and New Guinea after the war until his retirement. His son—also Pastor Sogavare—continued his work in Papua New Guinea.

Oti Maekera and Robert Salau

As a young man Robert Salau was attracted to the civilized way of life of the European Christians he encountered—a life without killing and a constant fear. He desperately wished to attend school, but his father was solidly opposed. No son of his would follow the “east wind” of the white people. Instead of arguing with his father, he ran away to school, leaving his island of Doveli.

Oti Maekera was the Jones’s houseboy and Salau, a teacher, had recently lost his young wife, when in 1929 Pastor Jones travelled to Rabaul with Oti and Robert. Oti was stationed at Rabuane, while Salau was at the mission at Bai. Even though as a young teacher, Robert had lost his young wife and a child had died, he continued to have courage and faith.

In 1930 Oti and Salau were working with Arthur and Nancy Atkins in Matipit, near Rabaul, the unofficial headquarters of the mission work in New Britain. Salau was sent to Emirau, while Oti, with four young helpers, ministered on the larger island of Mussau. They were joined by the Atkins, who together converted most of the population to the Seventh-day Adventist message. Translation work, pastoral visitations and establishing a school and clinic, was their focus.

Later in the 1930s, Oti and Salau were sent into the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea for the purpose of purchasing land for the mission. In the area around Kainantu, they built primitive shelters as their base. Without knowledge of the local languages, the men used their picture rolls and pointed to Jesus. Oti, with his guitar and Salau, with his ukulele, sang songs about the message of the story of Salvation.

During the war, Robert Salau with his second wife Pizo, were isolated on the island of Emira, New Ireland. For two-and-a-half years, they encouraged the members despite the Japanese occupation of the island.

In 1949, Andrew Stewart was invited to the United States to follow the camp-meeting circuit. He chose to take Robert Salau with him. The men had a wonderful time sightseeing, faith sharing and friendship renewing and mission reporting as they told hundreds of people around the world of the advancement of the missions in the South Pacific.

Deni Mark

Deni Mark, a Solomon Islander, was working in Mussau of the north coast of New Guinea when he was transferred to Kambubu, 55 km south-east of Rabaul, on the island of New Britain. Deni and his wife Ellen were greatly appreciated by the students, the teachers and local community. Deni led groups of students into the Baining area, assisting in medical and evangelic work.

Life changed dramatically when the war erupted. By a government decree, the Australians were evacuated to Australia, so in 1942 he was appointed acting principal of the school. He took the students into the jungle away from the Japanese soldiers who occupied the area around the school. Life was difficult for the families and students as they hid, tended gardens and worshipped in the jungle.

But life became even more dangerous as Deni assisted Allied servicemen, providing food and shelter, gathering intelligence for the Australian Coast Watchers, providing maps of Japanese positions and equipment, and arranging the rescue of Allied airmen who had been shot down. He also helped many Chinese who had fled the invading Japanese forces. But he never forgot that first of all he was a missionary of God, praying with the soldiers, sharing literature and encouraging the soldiers to worship God.

When the Japanese became suspicious that Deni was providing information to the Allied soldiers, he was arrested and on several occasions severely beaten. Eventually he was imprisoned in a water tank. This led to health complications, which weakened him. He became ill and died in September 1944. He was buried by workers from Mussau on the banks of the Kambubu River, metres from his prison cell. His grave is still honoured by the Baining people to whom Deni brought Christianity. A new library at Kambubu High School was named in his honour in 2003.

Reference:

Boehm, K. (2006). No greater love: A tribute: Deni Mark Megha, a pioneer Solomon Island teacher and missionary in the New Guinea Islands, 1933-1944. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 6(1). Pp. 38-41.

Sasa Rore

Sasa Rore was born at Dovele on the island of Vella La Vella, Solomon Islands, in 1928. As a graduate of Betikama Missionary School, he began his service for the Seventh-day Adventist church as a part-time teach for the same institution. Two years later, he and his wife Mary began full-time employment. When war came to the Solomon Islands and all expatriates ordered to leave, Sasa Rore in Guadalcanal was allowed to stay. He looked after his flock, but also rescued many Allied soldiers fleeing the Japanese occupation forces.

Following the war, he served the church in a variety of positions: assistant Education Director for the Bismark-Solomons Union; Headmaster of the Boliu Central School, Mussau; Secretary-Treasurer, Education and Missionary Volunteer Secretary, North Bismarck Mission in Kavieng; and similar positions in Lorengau for the Manus mission; the Bougainville Mission in PNG and back to the Solomon Islands to complete 40 years of service.

Sasa was an astute administrator who inspired his workers to push the frontiers of the Adventist biblical message into new areas.

Reference:

Rore, Nathan. (2004). Out of tragedy, a new hope: early developments at Dovele on Vella La Vella in the Solomon Islands. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 4(2). Pp. 20-22.

Timeline in the Solomon Islands of the Advancement of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

| 1914 | Griffith Frances and Marion Jones arrive in the Solomon Islands on the Advent Herald Chiefs and influential landowners impressed with the cleanliness of the mission and their use of English |

| 1929 | Batuna Training School established Purchase of Minando to enagle Nicholson to move quickly about the lagoon and visit pockets of interest |

| 1917 | Melanesia commissioned, sailing as far as Vanuatu, Papua and New Quinea over nearly 30 years Missionaries break down animosities and foster a church community spirit resulting in many baptisms Many of new converts are young, zealous and dependable and achieve amazing results |

| 1920 | Considerable changes made in European staffing: all of the pioneer missionaries experienced repeated bouts of malaria, dangers on the stormy seas, primitive housing facilities and isolation The first decade of the Solomon Islands Mission saw the establishment of key stations staffed by Europeans; at these mission stations young men were briefly trained to care for branch stations Batuna became a training school with a printing press leading to the publication of pamphlets and two hymnbooks |

| 1924-1927 | Batuna gradually assumes headquarters status Two government officers and most of their police guard and boat crew murdered while collecting taxes not far from the Andersons’ station. For weeks the Anderson family live on the Advent until calm restored |

| 1930 | Almost 600 baptised members in the Solomon Islands – doubled before World War II and increased more rapidly after; Solomon Islands prove to be most responsive groups in the South Pacific |

References:

Anderson, J. D. (1/12/1935). Meeting Jugha and his native teachers. Australasian Record. P. 3.

Boehm, K. (2006). No greater love: A tribute: Deni Mark Megha, a pioneer Solomon Island teacher and missionary in the New Guinea Islands, 1933-1944. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 6(1). Pp. 38-41.

Eager, Yvonne (2007). Turmoil, peace, recovery and restoration in the Solomon Islands: the joy of missionaries returning. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 7(1), pp. 14-18.

Ferch, A. J. (Ed). (1991). Journey of Hope. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists.

Hare, R. (1950). Fuzzy-Wuzzy Tales. Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald.

Hawkes, L. & Billy, L. (2008). Brian Dunn- Adventist Martyr on the island of Malaita in the Solomon Islands- 1965. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 8(1). Pp. 28-31.

Hook, M. Vina Juapa Rane: Early Adventism in the Solomon Islands. Booklet 29: Seventhday Adventist Heritage Series. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division Department of Education.

Letter from Pana (7/3/1938). Australasian Record. Pp. 3, 4.

Missionary Address by Pastor Wicks and Pana (18/10/1926). Australasian Record, pp. 26-31.

Pana, Barnabas. (9/2/1925). A letter from Pana. Australasian Record. Pp. 3, 4.

Piez, E. (2007). Atoifi Hospital, Malaita: its planning, construction and opening in the 1960s. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 7(1), pp. 19-27.

Reye, A. (2006). They did return! The resumption of the Adventist Mission in the Solomon Islands after World War 11- Part 1. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 6(1), pp. 49-56.

Reye, A. (2007). They did return! The resumption of the Adventist Mission in the Solomon Islands after World War 11- Part 2. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 7(1), pp. 5-13.

Reye, A. (2014). Raiders on the horizon: Chivalry in the Pacific theatre in WW11. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 10 (1), pp. 21-23.

Richter. R. W. (2005). Betikama Missionary School: consolidation and progress in the 1950s. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 5(1). Pp. 4-9.

Rore, Nathan. (2004). Out of tragedy, a new hope: early developments at Dovele on Vella La Vella in the Solomon Islands. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 4(2). Pp. 20-22.

Steed, E. H. J. (2012). Impaled: The story of Brian Dunn, a twentieth-century missionary martyr of the South Pacific. Nampa. Idaho: Pacific Press.

Tanabose, L. P. (2010). Ghoghombe: land identified for God’s kingdom. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 9(1). Pp. 4-7.

The story of two lives: Pastor Nathan and Mrs Mary Rore. (2010) Journal of Pacific Adventist Journal. 9(1), p. 39.

Thrift, L. (2003). Post-war Batuna: Revitalising the Marova Station in the Western Solomons. Journal of Pacific Adventist Journal. 3(2). Pp. 10-13.

Thrift, L. (2004). Exciting yet purposeful: a new venture in the Solomon Islands: the birth of Betikama Missionary School, 24.12.47-30.01.49. Journal of Pacific Adventist Journal. 4(1), pp. 18-21.

Wicks, H. B. P. Galokisa, the busman of Chiseul. (28/5/1923/) Australasian Record, p. 4.

Wicks, H. B. P. (4/6/1923). Taki, the old man of Chiseul. Australasian Record, p.

Wicks, M. (4/2/1924). Marriage of Peo. Australasian Record, pp. 2, 3.

Extra stories

Tauku—from the Solomon Islands to Papua

Tauku and his wife Jesi arrived in Papua in December of 1935. After spending six months in Mirigeda in order to learn Motu, they were located at Belepa in the Vailala area. Tauku was an efficient teacher and great preacher-pastor, visiting from house to house sharing the gospel. Tauku used his musical talent to teach people to sing gospel songs.

Tauku was one of the three Solomon Islanders given instruction in church work, ordained and entrusted with leadership responsibilities in the Vailala area when the Australian and New Zealand missionaries were compelled to leave Papua during the war. Pastor Tauku continued his work in Papua through the war years and afterwards until he retired in the Solomon Islands in 1957.

Ngava

Ngava was an experienced ministerial worker and member of the Solomon Islands Mission Committee when called to work in Papua in 1939. He had been selected to take over the leadership of the mission work in Papua if the war situation should lead to the evacuation of the European missionaries. As Assistant Mission Superintendent to Pastor C E Mitchell, he was based at Mirigeda, visiting other mission stations in the mission boat Diari. Because of the war situation, Pastor Ngava found it necessary to leave Mirigeda. He moved to Korela, where he added school teaching to his other duties.

References:

Ngodore Sogavare Loko: Anderson, J. R. (1991). Seventh-day Adventist Fijian, Cook Island, Australian Aboriginal, and Solomon Islands Missionaries in Papua: 1908-1942. In A. J. Ferch, (Ed). Journey of Hope. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists. pp. 139-140

Tauku: Anderson, J. R. (1991). Seventh-day Adventist Fijian, Cook Island, Australian Aboriginal, and Solomon Islands Missionaries in Papua: 1908-1942. In A. J. Ferch, (Ed). Journey of Hope. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists. p. 140.

Tutuo: Anderson, J. R. (1991). Seventh-day Adventist Fijian, Cook Island, Australian Aboriginal, and Solomon Islands Missionaries in Papua: 1908-1942. In A. J. Ferch, (Ed). Journey of Hope. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists. P. 140.

Iri Solato: Anderson, J. R. (1991). Seventh-day Adventist Fijian, Cook Island, Australian Aboriginal, and Solomon Islands Missionaries in Papua: 1908-1942. In A. J. Ferch, (Ed). Journey of Hope. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists. P. 140.

Ngava: Anderson, J. R. (1991). Seventh-day Adventist Fijian, Cook Island, Australian Aboriginal, and Solomon Islands Missionaries in Papua: 1908-1942. In A. J. Ferch, (Ed). Journey of Hope. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists.p. 140.-142.

Edith (Guilliard) Carr: Litster, W. G. (1997). Avondale’s Pioneer Women Missionaries. In B. D. Oliver, A. S. Currie & D. E. Robertson (Eds.). Avondale and the South Pacific: 100 Years of Mission. Cooranbong, NSW: Avondale Academic Press. P. 53-55.

Colporteur Stories: Reference: Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm. pp. 56-56.