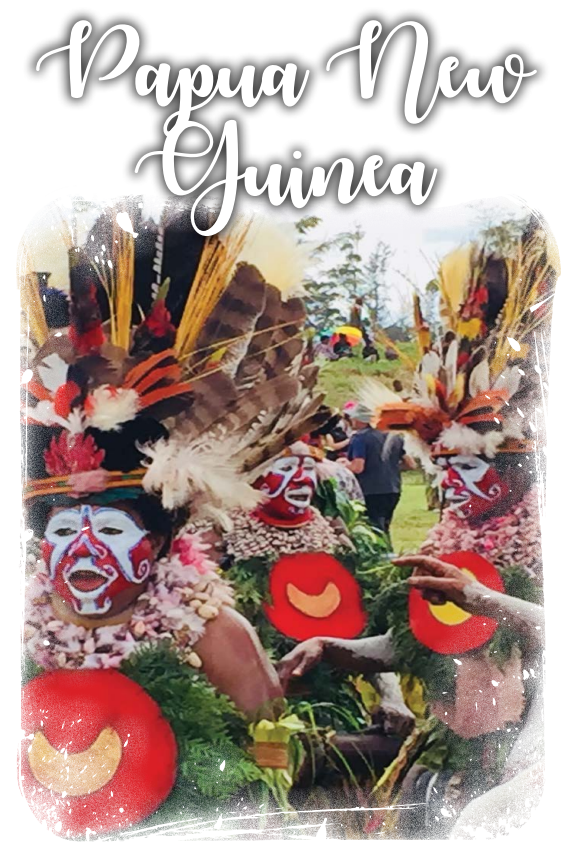

Papua New Guinea

Content:

From 1902 to 1905, Adventist church leaders, such as Edward Gates, Griffith Jones and George Irwin sailed into New Guinean and Papuan parts en route to other parts of the world. These visits heightened their desire to place Adventist missionaries among the people.

Papuan Mission

In 1906, church officials in Australia allocated one quarter’s Sabbath School offerings for a Papuan Mission fund. Septimus and Edith Carr, with Benisimani (Benjamin) Tavondi as their Fijian assistant, were assigned to Papua. They arrived at Port Moresby in 1908. They were the first Seventh-day Adventists in Papua. Because of the Comity Agreement, an arrangement dividing the country into geographical

spheres of church influence, the SDA church was discouraged from establishing a mission in the country. Eventually these missionaries established his training school and mission station at Bisiatabu on the Sogeri Range near Port Moresby.

In 1910, Fulton organized the missionaries into a church during a one-day stopover en route to the East Indies. There were six charter members: the Carrs, the Smiths, and Beni and Salomona Tuaine from the Cook Islands. But church growth was painfully slow.

Carr and other missionaries tried to learn the Koiari language from employees on the mission farm. One of these workers was named Faole. He was eventually given a picture roll to take to his mountain home near Efogi so that he could conduct services.

It was Beni who first tried to generate an interest in Christianity among the tribes in the Owen Stanley Ranges. Two more Fijian missionaries arrived in Papua in late 1913. They were Mitieli (Mitchell) Nakasamai and his wife Fika. The following year the Carrs returned to Australia because Edith was ill. They had pioneered in Papua for six years in difficult conditions. The Lawsons remained at the Bisiatabu station,

assisted by the two Fijian couples. This situation remained throughout the years of World War I.

The years 1914 to 1920 were ones of stagnation in the Papuan Mission. Young men continued to work and attend school on the plantation, but none made a commitment to Christ. Then late in 1918 a tragedy occurred at the Bisiatabu station when Beni was bitten leg by a venomous snake and died. Church administrators were beginning to lose faith in the Papuan venture. Griffiths and Marion Jones were asked to go to Bisiatabu in 1921 and were united with Mitieli and Fika. Jones, together with his Fijian helpers, doubled their efforts to influence the local people. By the time the Joneses left at the end of 1923, there remained a promising group of about 20 students.

The Jones were replaced by Gerald and Winifred Peacock. Will and Mollie Lock and nurse Emily Heise were appointed to pioneer the work at the Efogi station, while the Peacocks remained at Bisiatabu. Albert Bateman arrived to assist, while from Fiji came Nafitali (Naphtali) Navara and his wife Vasiti (Vashti), who replaced Mitieli and Fika.

A highlight of 1926 at Bisiatabu was the conversion of Meanou and his wife Iamo. Meanou, who had had previous contact with the Carrs. He offered land on the coast at Tupuselei, which later became a training school. During this time, there was serious Motuan translation work undertaken by Lock, Engelbrecht and Meanou.

Lock then procured land at Korela on the Marshall Lagoon, together with a small block at nearby Aroma. The Mitchells transferred to Korela, leaving the Fijian couples in charge at Efogi. Mitchell chose Faole to help him establish the new station and together they conducted a school for the people of Wanigela Village. Gradually a wide network of mission stations along the coastal regions developed.

The collapse of the Comity Agreement opened vast opportunities. It meant that the Adventist Mission could work in more densely populated areas in contrast to the sparse Koiari territory. Some stations were supervised by Fijians or locals. Faole and his wife, for example, later returned to Efogi and ministered to their own people.

New Guinea Mission

Concurrent with this renewed thrust in Papua, a mission offensive was being made from the Solomon Islands, with a mission station planted on Bougainville Island. It was from there that the Adventist mission spread to New Britain and northern mainland New Guinea. Within a year, whole populations accepted the Adventist message. One of a ship’s crew, Tong, returned to the Admiralty Islands. Due to his positive influence, a teacher arrived and within three years there was 560 Sabbath-keepers on the islands.

Later, in 1934, a start was made in the populous highlands of mainland New Guinea, first at Kainantu (then named Ramu), followed by Omaura and Bena Bena in the Eastern Highlands. By 1940, Adventist missions had been active in Papua for 32 years and had some 1780 converts. In contrast, 16 years of work in New Guinea had produced 4000 converts.

Gilbert McLaren captained the Veilomani in 1930 to the St Matthias group of islands, north of the New Guinea coastline. He was warned not to go to Mussau as “no white man have ever come away from Mussau alive.” There was a common belief that the Mussauns were regarded as rather volatile and unpredictable, and maybe even cannibals. The chiefs of each village were adamant that the missionaries could not leave a teacher. However, one chief was so impressed by the singing he heard at the evening worships aboard the Veilomani that he agreed to a teacher as long as the teacher would teach the people to sing. Gilbert McLaren sent two Solomon Islanders, Oti and Salau to Mussau—both gifted musicians and singers. Within a year, the whole population accepted the Adventist message.

Pastor McLaren was never afraid to venture into areas that other missionaries had never been. After successfully establishing mission stations in the St Matthias group of islands, he took his missionary spirit into the highlands of New Guinea, with plans to establish a mission station in the Kainantu district. Again he took Oti and Salua with him. When a mission was established, he moved to new locations, allowing

others to stabilize the work.

Mission during WW2

In 1941, the Australian Government directed that all women and children be evacuated from Papua and New Guinea. When the World War 2 broke out in the Pacific, Europeans were hurriedly evacuated. Not all the mission vessels succeeded in escaping. The Veilomani was sunk and the Malalagi was intercepted by a Japanese destroyer. The Diari arrived in Cairns and the Melanesia eventually arrived in Sydney.

Trevor Collett, a self-supporting missionary, from Emira, stayed in Rabaul to nurse his friend, Pastor Arthur Atkins who was working in the St Matthias Islands. Pastor Atkins died in the hospital at Kokopo, outside Rabaul. Trevor Collett, Mac Abbott, the superintendent the New Guinea mission, and Len Thompson, an Adventist who worked for Australian government were captured by the Japanese and became prisoner of wars. They, with 1050 other Australians died when the Japanese prison ship Montevideo Maru was torpedoed by a United States submarine on July 1, 1942.

Faole

Faole was born in the village of Bagaiunumu, high in the Owen Stanley Range of Papua, in a tribe proud of their ancestral headhunting and cannibal ways. By the age of 15, Faole had proven his manliness by killing a man. It so thrilled him, he continued to kill and gained the reputation as an evil and fearless man. Following the death of his mother died, he was arrested, put on trial but eventually returned home.

Returning to his local district, he discovered great changes. In 1910, the Seventh-day Adventist church had established a mission station at Bisiatabu, on the edge of the Faole’s mountain range. Faole asked the missionary for work, but the missionary had heard of Faole’s criminal past. Years later, Faole again asked to work for the mission. The missionary was suspicious and tried to discourage Faole from coming to the

mission. This time Faole refused to accept the missionary decision. Faole refused to leave the mission. Faole was given a plot of ground, built his own house and attended school. Due to his friendliness, people came to see if this former criminal had really changed.

When the SDA church wished to start a mission on the coast, the white missionary asked Faole to assist him. That was the beginning of Faole’s missionary endeavours. He moved from place to place with his family. He insisted on a well organised village, with a church and a school in the middle surrounded by clean houses, beautiful flowers and extensive gardens.

At one village, the headman was worried that Faole was discouraging traditional heathen practices. When the chief suddenly died, the old men could not find a reason for this sudden death. Blame was placed on Faole. The plan was to kill Faole and his whole family. Fifty experienced fighting men, with their tipped arrows and sharpened spears were ready to invade the village. There was one old man who respected what Faole had done to improve the village. He secretly set out to warn the white missionary telling one man from Faole’s village that trouble was coming. The old man convinced the white missionary that Faole was in trouble, so they hurried to help him.

Upon arriving at Faole’s village, they were stunned to see Faole alive.

Faole told them his story. One afternoon he sensed trouble. Even at evening worship, the people appeared anxious. The family returned home and read Psalm 34:7. After asking God for forgiveness for his anxiety, and for protection, he went to bed, confident in God’s protection.

The white missionary was puzzled, so he travelled to a nearby village. He heard that the 50 men returned from their planned night raid to Faole’s village trembling and scared. The men admitted they were scared when the saw Faole’s house guarded by men in white clothes throughout the whole night. Faole knew that God had protected him.

Even when Faole was an old man, he continued to work for the church. He was sent to Enevologo, beyond Efogi, in his home district on the Owen Stanley Range to start a new mission. The problem was that the Japanese had begun their military drive south along the Kokoda Track.

One night, Faole had a dream that the war had started, and he need to protect his people. He rose early and took all his people to the other side of the river and told them to hide into the jungle. The next day the Japanese bombed and gunned his house.

With his adopted daughters, he refused to run away. From the shelter they had built overlooking the river to the village, they could see the fighting between the Japanese and the Allied forces. Faole kept reciting John 14:1-3. In another dream, Faole sensed danger, so they fled. Their new home and the whole village was bombed by enemy planes.

Hiding in the jungle, he kept up his routine of regular worship. He invited Allied soldiers who were trying to escape the enemy to have worship with him. He invited the soldiers to join him singing, “Anywhere with Jesus I can safely go.” Faole would feed the soldiers and care for any seriously wounded soldiers. When one soldier died, Faole insisted on a Christian burial.

When a group of soldiers was lost, He offered to guide them out of danger. It was a scary journey avoiding the enemy on all the major tracks. Faole would lead the soldiers, while the girls would follow covering up the footprints. On Sabbath, Faole insisted on opening the Sabbath with worship and remaining still over the Sabbath day. This provided an excellent opportunity for Faole to explain Bible verses and to talk about Biblical prophecy. After days of travelling the groups was tired and hungry. Faole left the girls in a safe place and admitted he was lost. Instead of showing despair, he asked the group of weary, tired and hungry soldiers to pray to God. At the end of the prayer, Faole rose and turned in the opposite direction. The soldier followed. In less than an hour, they soldiers were safe. Faole refused any money for his services but took some food and returned to support his own people. As the war continued, he and his family cared for the Allied soldiers.

When the war ended, Faole gathered his converts and took them to the mission station. He left and returned to the mountains to continue serving his God.

John Masive

John Masive was born, people were still very primitive. The people covered their bodies with pig’s grease and were involved with fighting people from other tribes. People would cut off fingers of dead people and hang them around their necks. These people lived at a place called Bena Bena. When white government officers came to his village, the people thought they were gods. When white missionaries came to the village, the people were confused. How could these people be gods when the

missionaries talked about worshipping gods!

One day John Masive went to the new mission station that was established near his village. He was warned to be careful about white people as they were not gods, as they first thought, but cruel and violent men and would take all their food and tobacco. Instead of being rude, the white missionary spoke nicely to him and gave him food. He decided to stay and attend the school at the mission station.

Masive learned well at school and wished to attend the next level of schooling at Omaura. The people of his village, tried to discourage him, but he went anyway. Masive enjoyed the school and encouraged other boys and girls to attend school.

Things were going well at Omaura when the World War 2 broke out. The white missionary teachers at the school were forced to leave and return to Australian. Local PNG teachers continued to manage the school. Guibau took charge of the work in the area. The government officers came to the school and advised that they the teachers and the students needed to leave and move deep into the bush. Away from the advancing army, the students and the teachers built a new church and school and continued with the training. A patrol officer found the students and the teachers and accused them of running away, but Masive explained that they had continued their schooling. Eventually, the group was allowed back to Omaura, cleaned the school and replanted the gardens. To celebrate the return to the school, a baptism was to be held. Masive really wanted to be baptised.

One night he had a dream. In the dream he was digging a hole in a hard road. He looked at the pile of soil that he has thrown out of the hole. The dirt vanished and was replaced with a great company of people. In consulting Guibau, he was told that his dream meant he had trouble breaking his traditional and cultural habits. If he let go of these traditions, many people would follow him. He was baptised the next day. He was the first highlander to be baptised, but he opened the way for others. Hundreds of

people from Kainantu, Omaura, Bena, Kabiufa, Chimbu and Wabag eventually heard Masive preach, and they too were baptised. Masive became a great evangelist for the Seventh-day Adventist church.

Reference:

Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm. pp. 78, 88-89.

Manatau:

Pr Stanley Gander, an Australian missionary, was forced to evacuate his post in Madang on the north coast of New Guinea when the Japanese invaded the area. He left his Adventist Mussaun congregation in the hands of Manatau, from Buka Island. Even when a Japanese captain forbad the church members to continue their worshipping on Saturday, they worshipped in their usual fashion. When the captain realised that he was not obeyed, he marched into the church ready to behead Mamatau. Instead of bowing to the soldier, Mamatua told the officer that he was willing to die. This startled the officer, so he allowed the people to continue their worship. In telling the story, Mamatua, proudly proclaimed that he was like Shadrach, Meshack and Abednego.

Tati

During the war, the mountainous area around Rumba in Bougainville was invaded by Japanese soldiers. Pastor Tati, a faithful Solomon Island teacher was left in charge of the region when Cyril Pascoe. His role was to protect his students, church members and some Mussau teachers that were working at the school. He hid his group of people by hiding in rocky hideouts, clinging to the side of the mountains for more than 18 months. He was known as the “king of the Seven-days.”

Eventually his whereabouts was revealed to the Japanese. Tati prayed for safety as bombers dropped some 32 bombs around them. The people have no idea how they survived as they hid in a clump of bamboo.

When Pastor Tati was District Director on the island of Tang on the eastern side of Manus, he was not a young man. In the boat the Fidelis he would visit people on the island and tell them about Jesus. When news of the war came, the people did not know what this meant.

When the first of the Japanese arrived on Manus, there were still Australian soldiers about, although on a different part of the island. The local people were not afraid of any of the soldiers at the beginning. The problem was that the people did not know who was the enemy. Messages in in pidgin were dropped from planes identifying the Japanese as the enemy, but people still did not understand.

When the American came, no one was safe, including the Japanese. Many people thought they could hide in the bush, away for the bombs and bullets. Many Japanese died. The Australians and the Americans created airstrips Momote, Mogrin, Pitilu, Korinat and Avatuponam, recruiting local people to help build bush material houses. The workers were thrilled, as they were given clothing and food. But they refused to work on Sabbath, as it was their holy day. The soldiers argued they could have Sunday off instead. But many were forced to work despite their protests.

Reference:

Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm. pp. 35-36.

Laippai, Laia (1.987). Narration of Life’s Experiences. [Transcript of a taped story].

Rarioi

Rarioi was just a lad from Buka when the Japanese took many young men to work for them. One day when they lined up to receive their pay, Rarioi an older teacher, noticed a machine gun pointing at them. In their native language, he told to young me to run when he gave the signal. This they did, the soldiers opened fire killing a number of them. Rarioi was bayoneted and left for dead, a gash in his side. When the

Japanese left, Rarioi was taken to a house, sewn up without anaesthetic and bandaged.

The incident failed to discourage Rarioi for being a missionary in Bougainville. He heard that a mother in the south of Bougainville threatened her son with the threat that she would give him to the devil. The second time she threatened him, a terrible smelling being snatched up the child and ran away. Rarioi quickly followed to rescue the child from the being. Several times, Rarioi tried to grab the child, but was pushed away. He refused to give up and eventually the child was dragged free and carried

back to the village.

Rarioi knew that God was in control and whatever happened God would be supreme.

Reference:

Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm. P. 36.

Introduction: SDAs in the South Pacific (1885-1985)

First church in Australia

On May 10, 1885, 11 Americans set sail on the Australia from San Francisco, USA, with plans to establish the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Australia. The pioneer workers included Pastor Stephen Haskell; Pastor Mendel Israel, accompanied by his wife and two daughters; Pastor John Corliss, accompanied by his wife and two children; Henry Scott, a printer from Pacific Press; and William Arnold, a colporteur.

They arrived in Sydney on June 6, 1885. While Pastors Haskell and Israel stayed in Sydney, the others continued aboard a coastal steamer to Melbourne, which had been selected to be the base for the Church’s Australian activities as there were rumours of Sabbath-keepers living there. They formed the first Seventh-day Adventist church in Australia in Melbourne on January 10, 1886, with 29 members.

First church in New Zealand

Pastor Haskell, who was keen to spread the message in New Zealand where the pioneers had called on their initial voyage to Australia, returned to Auckland and began distributing the Church’s outreach publication The Bible Echo and Signs of the Times. Reports of Haskell’s successes in New Zealand caused the leaders of the Church in America to delegate A G Daniels, an evangelist, to travel to New Zealand to develop the work further. Daniels, an enthusiastic preacher, had great success and in 1887 opened the first Seventh-day Adventist church in New Zealand at Ponsonby. Daniels would eventually go on to become the world president of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

First Adventist contact in the Pacific Islands

In 1886, John I Tay, an American layman, reached Pitcairn Island aboard a vessel of the Royal Navy. He stayed on the island until another ship arrived. Tay’s simple teaching fascinated the islanders as the message matched with the message of literature—Signs of the Times—sent years previously from America by James White and John Loughborough. Within weeks, the islanders accepted the suite of Adventist truths. When Tay left, he promised to send someone to baptise the group.

Upon his return to America, Tay’s accounts inspired other Adventists to visit Pitcairn. One, Pastor Andrew J. Cudney, found an old schooner, the Phoebe Chapman, and he and a crew sailed for Tahiti where they planned to pick up John Tay before sailing to Pitcairn Island. Sadly, they never arrived, as the ship was lost at sea.

Tay was anxious to return to Pitcairn Island and a boat was required. Funds from Sabbath Schools across America raised money for one, the aptly named Pitcairn, which under Captain Joseph Melville Marsh, was ready to sail in October 1880. Tay was joined by two other enthusiastic missionary couples, Edward Gates and the Albert J. Read, who were greeted enthusiastically by the islanders on Pitcairn. Eighty-six people were baptised and a church formally organised.

When the Pitcairn departed the island three weeks later, on board were three Pitcairn Islanders who wished to spread the Adventist faith. As the ship travelled westward from island to island, literature was distributed, evangelical meetings held, and medical treatments dispensed. After visiting Papeete, the Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga, Fiji and Norfolk Island, it arrived in Auckland, New Zealand. There they

heard the news of Tay’s death in Fiji. The Pitcairn returned to California, carrying missionaries on five more Pacific voyages.

Australian and New Zealand missionaries to the Pacific

From those voyages into Polynesia missions were established in Pitcairn, Tahiti, Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga and Fiji. Most of the next wave of missionaries had their origins in Australia and New Zealand. But the work was difficult and met with resistance, with the London Missionary Society and Roman Catholic Church having made the initial impact on the islands.

SDA Mission after WW2

Until 1934 there were still fewer than 50 baptised members in the Papuan and New Guinean regions. Six years later, this had jumped to more than a thousand, due largely to the increased opportunities for expansion that had begun in the late 1920s. Growth has sky-rocketed since World War 2.

Many missionaries arrived from Australian and New Zealand to support the local PNG missionaries. Many of these new arrivals bought new ideas. One missionary, Lenard Barnard, introduced the use of aeroplanes to service the highlands of New Guinea. Leonard Barnard was the first missionary pilot for the Seventh-day Adventist Church. He cofounded the aviation company used by the South Pacific Division.

Barnard, known to many as Len, decided to become a missionary on his first visit to Papua New Guinea during World War 2 when he served as a medic in the Australian Infantry Forces. One day, he was ordered to examine 50 local men who worked as carriers for the Australian military. These men had barely survived an arduous trek through the jungle. The men were malnourished and suffering from various tropical diseases. But the last six men, while weak, were noticeably healthier and happier than the rest of the group. After quizzing the six men, Barnard learned that they were fellow Adventists who had learned about Jesus from foreign missionaries. During the trek, they had declined to eat unclean wild animals caught by the party and also worshiped daily. It was the striking contrast between the mission lads and the other carriers, motivated Barnard to become a missionary.

He returned to Papua New Guinea 16 years later as a medical missionary, building and operating a leper colony at Mt Hagen in the island’s Western Highlands. He spent 30 years serving as a pioneer missionary but said his greatest joy as a pioneer was to fly the first Adventist mission plane to go into service anywhere in the world. In the 1960s, he co-founded Adventist Aviation, a company that operates a fleet of mission planes in the South Pacific. The first plane was named Andrew Stewart, in honour of a well-known island missionary and administrator in Fiji and Vanuatu, and at the church headquarters in Sydney.

In the early 1950s, two Americans, Pastor J L Tucker and his son Laverne, visited Len Barnard in Mt Hagen Hansenide Colony. Pastor Tucker was preaching the gospel on the radio through “The Quiet Hour” program, promoted the “lands that time forgot” to his listeners. In response, some 6000 people contributed to the purchase of a new Cessna 180, the second plane in Papua New Guinea, christened Malcolm Abbott.

Other pilots followed Barnard in Papua New Guinea. Missionaries were dropped at small airfields around the country, from where they walked the valleys and ridges visiting church members, conducting training programs, baptising new converts and conducting marriages. The missionaries would return to the airfield a week or so later to be picked up and placed in another valley or to return home. At other times, the

mission planes were used for medical emergencies.

Local Papua New Guinea missionaries were most instrumental in expanding the influence of the Seventh-day Adventist Church throughout the country.

Lui Oli

Lui Oli was born in 1923 into a Papuan Hula speaking coastal village of Irapara, west of Port Moresby. As young boy, he first heard about Jesus when missionaries Galama and Kila Pau visited his village. Lui was so interested that he followed them to the mission school at Pelagai, 70 kms from his village. He completed classes to Grade 3, then attended Mirigeda Training School, 30 kilometres for the capital for the next two years. Lui was so impressed by the knowledge of Jesus Christ and the Lord’s imminent return that he was baptised in 1939 and wished to work as a missionary.

Soon after, in 1941, the Japanese entered the war. All the Europeans were sent to Australia. As the missionaries waited to board the mission boat, the Diari, in Port Moresby, the first Japanese bombs dropped on the city. The expatriate missionaries eventually departed, but young and inexperienced Lui was left at Mirigeda mission station with Pastor Ngave and Pastor Ope Loma.

Army personnel came to recruit carriers, Lui among them. At first, he cared for high ranking officers at Konedobu in Port Moresby, but he wished for more action and to assist the soldiers. God had other plans. When the expatriate missionaries returned in 1944, they immediately asked the army commander for any Seventh-day Adventists. Lui was thrilled to be back with his friends, especially Pastor Mitchell and Pastor

Campbell, as together they revitalised the mission work in various coastal villages. Lui’s wife of three years died of malaria and pneumonia. When Pastor Campbell was called to the Highlands, Lui, now regarded as an experienced teacher and missionary, was left in charge. He evangelised in various villages along the Aroma coast.

In 1947, he married Esther Pala Kila from his own village, becoming the proud father of a large family. During his ministry, his extended family also accepted the Adventist truths.

In 1953, he left the familiar coastal area and moved to the highlands to work at the newly established mission school at Kabiufa near Goroka. He was ordained in 1956, at which time he moved to the Western Province, then in 1957 went to Daru, embarking on mission work along the Fly River as a licensed captain of small mission vessels.

He was moved in 1964 to a new area, Kikori in the Gulf Province, with the mission boat, the Urabeni. In 1967, he went to Port Moresby as assistant to the mission presidents—Pastor Ernest Lemke, Pastor Lester Lock and Pastor John Richardson—before being appointed the president of the Central Papuan Mission in 1973.

As president, he travelled the district, attending camp meetings and preaching in a different village most Sabbaths. When in 1977, Lui became president of the Madang-Manus Mission, he travelled from island to island on the mission vessel, the Light, visiting his members.

Lui retired in 1980, but continued his missionary focus visiting church members, conducting evangelistic meetings, conducting baptisms and encouraging the building of local churches.

Reference:

Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm. Pp. 43.

References:

Lock, L. (2005). A Pioneer and Catalyst: Gapi Ravu of Eastern Papua. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 5(1). Pp.15-18.

Hook, M. Lotu Belong Sevenday: Early Adventism in Papua New Guinea. Booklet 32: Seventh-day Adventist Heritage Series. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division Department of Education.

Current Seventh-day Adventist Church

During the first 62 years (1908–1960) of the work of the SDA church, it progressed slowly, but by the year 2000, membership of the church had reached 200,000 mark.

Evangelistic projects

This was a result of a conscious effort of the administrative and local church levels to focus on evangelism projects: “The Bible Speaks” program, the church planting program called the “Grow One,” the satellite ministry, and colporteur ministry.

Schools and education work

These programs were complemented by the positive image of the church created by the church school system. After the war, the number of schools increased. Most villages had a small school and larger communities hosted a secondary school. Jones Missionary College, commonly referred to as Kambubu, expanded and trained many future missionaries after the war. The land for this school was purchased in 1936, but most of its original buildings were destroyed in the war. After the war, the school greatly expanded under the directorship of Doug Martin, with the school choir winning various singing competitions, spreading its influence.

Kabiufa Missionary School, established in 1949 to provide education for the Eastern Highlands students, then Paglum School in the Western Highlands Province, continued the tradition of the church providing boarding secondary schools.

Originally the school curriculum included Junior Missionary Volunteer programs, which later became Pathfinders. Many of these programs incorporated junior camps where there was an emphasis of spiritual revival and honour work. The first Junior Camp was held on a small island in the Boliu Harbour, near Mussau, under the direction of two brothers, Pr Hugh Dickins, the education liaison for the church, and Keith Dickins, a teacher at the Intermediate School on Mussau.

Reference:

Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm. p. 17.

As the educational level of the average church member increased, so did the need for more post-secondary education. Omaura provided training for rural pastors; Sonoma Adventist College then Pacific Adventist University trained future church workers.

As early as the 1960s, there was serious thought about introducing a full tertiary program that served the needs of the island union missions. Papua New Guinea was the logical position for this new institution due to the high population of PNG and the increasing number of SDA students. Eventually the site of a previous dairy farm was chosen for the new college. Its proximately to an international airport in Port Moresby was an added advantage. In 1979, the land became the property of the Seventh-day

Adventist church. The Pacific Adventist College was officially opened by the Prime

Minister Sir Michael Somare.

After the war, the number of health clinics expanded throughout the country. The Togoba Hansenide leper hospital near Mt Hagan transitioned into the Sopas Hospital and became a nursing training school. In 2000, Sopas was continuing to provide medical assistance although its nurse training component was transferred to Pacific Adventist University.

Aviation

Due to the mountainous terrain, the SDA church introduced planes to visit isolated villages and to assist in the medical work. The aviation program has been a successful initiative by the church.

Recent missionaries

As church members moved around the country, their Adventist zeal went with them. What must be remembered is the role of the Holy Spirit. Most Papua New Guineans did not become overseas missionaries but choose to remain in the country and spread God’s message throughout the country.

Aaron Lopa

Dr Aaron Lopa was one of Papua New Guinea’s foremost Church leaders and ministerial trainers —passed away in the early hours of Sabbath morning at Port Moresby General Hospital on April 20. He was 67 years old. A funeral service was held at Pacific Adventist University (PAU) on Sunday, April 28. The SDA Church in PNG mourns loss of this wonderful Adventist pastor who was one of Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) foremost Christian leaders and ministerial trainers.

The son of an animist “devil priest”, Dr Lopa made a significant impact on Adventism in the Pacific during his 40 years of active ministry. He spent a number of years serving at both Sonoma Adventist College and Pacific Adventist University (PAU) and was an integral part of the improvement of training for teachers and ministers. “For many ministers in PNG, Aaron has been both a model and a mentor,” said Dr David Thiele, acting deputy vice chancellor of PAU. “His influence in the Pacific will endure because Aaron profoundly influenced a whole generation of ministers, shaping their understanding of ministry, spirituality, and the Church’s mission.” “Aaron Lopa was truly sent by God to minister to me to enter God’s service,” said Pastor Thomas Davai, director of Student Services at PAU. “He began the fire burning in my heart and I wanted to be like him preaching [from a] very early age.” His influence in the Pacific will endure because Aaron Lopa profoundly influenced a whole generation of ministers, shaping their understanding of ministry, spirituality, and the church’s mission.

Reference:

Shanug, L. & Thiele, D. H. (2013). Church in PNG mourns loss of Adventist Pastor. Australasian Record. p.18.

Matupit Darius

Pastor Matupit Darius was a great leader over his 36 years of ministry in various places around PNG, including as the pastor of the Pacific Adventist University church from 2002 to 2003, and from 2010 until his death in 2014 as a lecturer in its School of Theology. He was a graduate of PAU, with Bachelor of Theology and Master of Arts (Theology) degrees.

He was an orator, writer and film maker. He is appreciated as someone who was an enabling leader and team contributor, with an ability to connect, challenge and teach all at once. Those who worked closely with him and his students were blessed by his generous and genuine mentoring, sharing of wisdom, sense of justice and compassion, which threaded through his interactions.

Reference:

Condolence Message: The late Pr Matupit Darius. Pacific Adventist University Web Page. www.pau.ac.pg/news-entries/5498

Papua New Guinea Timeline

| 1902-1903 | Early Adventist Church executives Edward Gates, Griffith Jones, George Irwin sail into New Guinea and Papua on way to other parts |

| 1906 | Australian Sabbath School offering assigned to Papua Mission |

| 1908 | Pr John Fulton, Vice President of AUC, calls Septimus & Edith Carr, Benjamin (Beni) Tavodi as missionaries to Papua from Fiji |

| 1909 | Bisiatabu chosen as site for new mission and lease signed in Carr’s name; rubber trees, pineapples and pumpkins planted |

| 1910 | Fulton organises missionaries into a formal church |

| 1911 | Arthur & Enid Lawson replace Smith First baptism of a boy, Taito Faole, a recent convert, conducts missionary work in his area |

| 1913 | Carr & Lawson explore mountainous areas behind Bisiatabu Arrival of Mitieli & Fika Nakasamai from Fiji |

| 1914 | Carrs return to Australia due to ill health |

| 1916 | Griffith Jones appointed director of Melanesian Mission incorporating Papua, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu Beni Tavodi dies from snake bite at Misiatabu |

| 1921 | Giffiths Francis & Marion Jones replace Lawsons Mitieli and Fika Nakasamai translate hymns into Koiari language |

| 1922 | Gerald & Winifred Peacock replace Jones |

| 1924 | Will & Mollie Lock, with Emily Heise, appointed to Efogi Nafitali and Vasitii Navara from Fiji replace Mitieli & Fika Nakasamai Large baptism at Bisiatabu |

| 1925 | Tevita & Livinia Daivalu arrive to assist Peacock |

| 1926 | Conversion of Meaaou & wife Famo who offer land at Tupuselei for a training school |

| 1927 | George & Chris Engelbrecht replace Peacocks at Vailala |

| 1928 | Cecil & Myrtle Howell appointed to Bisiatabu Meaaou translates Sabbath School lessons into Motu Tevita dies of blackwater fever Maika & Tokasa Dunika to assist Nafitali & Vasitii Navara at Efogi Engelbrecht, Watafeni and Luci, recent Koiari converst transfer to Bisiatabu Mitchells, assisted by Faole and Someli, transfer to Korela in the Marshall Lagoon |

| 1929 | Ross & Mabel Jones pioneer the Aroma Coast resulting in a network of mission station around Vailala, Korela and Aroma Jones, Oti and Salau from Solomon Islands establish a mission station at Matipit Island near Rabaul |

| 1930 | Arthur & Nancy Atkins replace Jones Missions stations opened on Emirau and Mussau Islands |

| 1937-1942 | Pr J S Gander sends four teachers from Kainantu to Madang |

| 1934 | Mission station at Kinanatu and soon there are stations at Omaura, Bena Bena and Sigoya Nationals, Taoha, Kohoi, Peter Pondek, Iwa become missionaries |

| 1945-1948 | K J Gray, Education Secretary of PNG & Principal of Bautama Training School |

| 1945 | Lester Lock first principal of Jones Missionary College (Kambubu), as the training school of Bismarck-Solomon Union Mission |

| 1950-1953 | Pr F T Maberly appointed Western Highlands president |

| 1955 | Pr Gapi Ravu appointed secretary at Oriomo, Gulf mission |

| 1958 | Jones Missionary College renowned for its male choir under choir master Pr Douglas Martin and conductor Solomon Islander Dan Masolo |

| 1961 | Kabiufa graduates teachers |

| 1965 | Pr Daniel Kuma appointed Bisiatabu District Director |

| 1972 | Aaron Lopa completes doctorate from Andrews University; returns as a Bible teacher |

| 1982-1986 | Pr Colin Winch Secretary and then President of PNGUM |

| 2008 | Central Papua Conference celebrate 100 years of Adventist mission |

| 2014 | Efogi and Koiari celebrate 100 years of Adventist mission |

References:

Atkins, Geoff. (n.d.) Mussau Memories: Story bilong family belong mipella. Self-published.

Aveling, I. (2006). ‘Not easy, but well worth-while’: reminiscences on life in the Western Highlands of Papua New Guinea over 50 years ago. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 6(1), pp. 35-37.

Barnard, L. (1969). Banish the night: Fighting Kur, Timango, and Other Devils in New Guinea. Mountain View, CAL: Pacific Press.

Barnard, L. (2014). White wings-empty oceans. Journal of Pacific History Adventist History, 10 (1), pp. 15- 20.

Boehm, E.A. (2010). Short stories from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, 1937-1963. Tumbi Umbi, NSW: Ken Boehm.

Caldwell, D. (2005). Our years in Kambubu: operating a boarding school on the island of New Britain in PNG in the 1970s. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 5(1). Pp.19-27.

Cavanagh, P. (2007). Beginnings: Through indigenous eyes: the entrance of Adventist Missions into the highlands of New Guinea. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 7(1), pp. 28-29.

Chapman. A. G. (2001). Breaking ground: the entrance of the Adventists into Papua New Guinea: Patience and perseverance. Overcoming the “spheres of Influence” policy to establish the first mission station at Bisiatabu, 1908-1914. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 1(1), pp. 11-16.

Chapman, A. G. (2002). Breaking new ground: Part 3: Finding a new way: success in spite of problems. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 2(1). Pp. 8-10.

Chapman, A. G. (2002). Breaking new ground: Part 4: the influence of the Solomon Islands Mission in Papua, Papua New Guinea, 1921 and onwards, Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 2(2), pp. 13-15.

Chapman, A. G. (2003). Breaking new ground: Part 5: The Kaiari School, Bisitabu, Papua New Guinea. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 3(1), pp. 12-15.

Chapman, A. G. (2003). Breaking New Ground: Part 6: Efogi Mission: Entering New Guinea. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 3(2). Pp. 6-9.

Chapman, A. G. (2004). Breaking new ground: Part 7: Mission Advance. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 4(1). Pp. 9-13.

Chapman, A. G. (2004). Forward thinking and practical plans: establishing raining schools in Papua and the Mandated Territory of New Guinea in the 1930’s: Part 8. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 4(2), pp. 9-14.

Chapman, A. G. (2005). Establishing Put Put and Omaura Training Schools in New Guinea: (1939, 1941): and an evaluation of the medical and educational work there: Breaking new ground- Part 9. Pacific Adventist History,

Chapman, A. G. (2006). Education: the church and the Administration: Breaking new ground. Park 10. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 6(1), pp. 11-17.

Davai, T. (2004). Meanou Peruka: providential leading in the spread of the Gospel: Papua in the early 1930s. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 5(2). Pp. 10-14.

Devine, L. D. (2002). Steps toward a unified University system for the Seventh-day Adventist Church in the South Pacific. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 2(1), pp. 34-37.

Ferch, A. J. (Ed). (1991). Journey of Hope. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists.

Gilmore, L. A. (2002), Providing for a permanent Adventist Presence in densely populated tribal areas: establishing and developing a mission station in South Simbu in the highlands of Papua New Guinea: 1948-1953. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 2(1). Pp. 15-22.

Guy, Wes. (2007). Adventist Aviation in Papua New Guinea: bridging valley and mountain boundaries, 1964-1980. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 7(1), pp. 55-61.

Hare, R. (1950). Fuzzy-Wuzzy Tales. Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald.

Hawkes, L. with Watson, B. (2012). When God Calls, Expect Adventure. Warburton, VIC: Signs

Hook, M. Lotu Belong Sevenday: Early Adventism in Papua New Guinea. Booklet 32: Seventh-day Adventist Heritage Series. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division Department of Education.

Jonathon R., & Tarburton, S. (2003). A dream and an inner voice: How the Seventh-day Adventist Mission came to Inland Wewak in the Sepik area of Papua New Guinea. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 3(1), pp. 8 – 11.

Lemke, E. (n.d.). When God intervened. Self-published.

Lock, L. (2005). A pioneer and catalyst: Gapi Ravu of Eastern Papua. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 5(1), 15-18.

Lopa, A. (2003). Adventism’s explosive presence: Factors influencing the growth of the church in Papua New Guinea from 1960-2000. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 3(1), 3-8.

Lopa, A. (1010). The isolated Western Islands of PNG: The Seventh-day Adventist church reaches the ‘Tiger People’. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 9(1), pp. 27-32.

Macaulay, J. (2006). Compassion and Treatment: the church’s mission to lepers at the Togoba Hansenide Colony, Western Highlands, Territory of Papua New Guinea, 1954-1959. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 6(1). pp. 18-21.

Martin, D. (2007). The influence of music of Jones Missionary College and beyond: Part 1. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 7(1), 49-54.

Martin, D. (2008). Influence of Music at Jones Missionary College and Beyond: Part 2. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 8(1). pp. 19-23.

Oli, L. Saved from a spear for service: my story in Papua New Guinea. (2006). Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 6(1). pp. 27-30.

Pascoe, J. (2006). A missionary nurse in Papua New Guinea: hundreds of babies delivered safely. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 6(1), pp. 31-24.

Pascoe, M. (2002). A formidable task: Advancing the mission of the church in Enga Province, Papua New Guinea, the varied work of a district director in isolated areas, 1959-1966. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 2(2), pp. 9-13.

Scragg, W. (1965). Kukukuku Walkabout and other stories. Washington, D.C.: Review and

Herald.

Speck, W. & O. Into the Unknown. Victoria Point, QLD: authors.

Stafford, B. (2004). Early days at Kumul: a missionary wife’s life on a PNG outpost, 1948-1950. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 4(1), pp. 14-17.

Stafford, C. R. (2002). God’s Provinces: establishing the work of the Adventist church in East Simbu in the highlands of Papua New Guinea: 1948-1952. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 2(1), pp. 11-14.

Walton, J-E. B. (2004). South Pacific Island Missions captivate the Barnards. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 4(2), pp. 4-8.

Wilkinson, R. (2001). Establishing Pacific Adventist College. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 1(1), pp. 4-8.

Additional stories

Meanou Peruka: PNG Missionary in Papua: Davai, T. (2004). Meanou Peruka: providential leading in the spread of the Gospel: Papua in the early 1930s. Journal of Pacific Adventist History, 4(2). Pp. 15-18.

Kairi Kekeao: an early Papuan Pioneer: Lock. L. (2008). Kairi Kekeao: an early Papuan Pioneer. Journal of Pacific Adventist History. 8(1), pp. 24-28.

Beni Tavodi: A Fijian who ministered in Papua: Anderson, J. R. (1991). Seventh-day Adventist Fijian, Cook Island, Australian Aboriginal, and Solomon Islands Missionaries in Papua: 1908-1942. In A. J. Ferch, (Ed). Journey of Hope. Wahroonga, NSW: South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists. pp. 129-130.

Edith (Guilliard) Carr: An Australian who ministered in Papua: Litster, W. G. (1997). Avondale’s Pioneer Women Missionaries. In B. D. Oliver, A. S. Currie & D. E. Robertson (Eds.). Avondale and the South Pacific: 100 Years of Mission. Cooranbong, NSW: Avondale Academic Press. P. 53-55.